Some of the things I remember about my family are most likely not altogether true. That is how an oral history is built: fiction is sprinkled into the batter along with the truth, browned and baked until it becomes something new, something edible.

My great-grandmother’s name was Hattie Will Redmond, but she was born Hattie Will Vestal, and went by Billie. She grew up in Pulaski, Tennessee, a place that still drips with a dark, muddy history and has the unfortunate distinction of being the birthplace of the KKK. Billie and Reggie left Pulaski separately, each when they were old enough. There is a photograph of them as children, dressed in white, seated on a mule, their pretty dark eyes peek out of the picture.

In a pocket of my memory my great-grandmother still sits on her red couch, wearing a pink pantsuit and a tiny, gauzy black scarf around her small neck. Her hair is set in the style she wore in the fifties, dyed black. She retired from a downtown department store, where she sold cosmetics. Her wrists, clothes, furniture, and hair always smelled like Shalimar, and her lips were always filled with lipstick. Her skin was immaculate; creamy and olive without wrinkles or blemishes. She glowed.

Her house was small, a true grandmother’s cottage, with a bright white kitchen with chrome edged counters. Oatmeal raisin cookies filled a ceramic cookie jar, and the white porcelain icebox always held a pitcher of Tang and a Pyrex container with lime Jell-o inside. Those were my father’s favorite treats when he was a boy, and she made sure to keep them on hand. She was my father’s grandmother, and he revered her as sort of angel/saint. He was her first grandchild, by her only daughter. My grandmother had met my grandfather through my grandmother; my other great-grandmother also sold cosmetics in the downtown department store, and the two women worked together often. They had a lot in common: both were career women when such a thing was rare, and they both had beautiful children around the same age.

There were things inside my great-grandmother’s house that frightened me, though she wasn’t one of them. Her bedroom was dark, often lit by candles, covered in off-white lace. On the dresser were framed photographs of her brother Reggie who had died and her son Bobby who also died. Both men were performers: her brother had left their home in Pulaski, Tennessee and became a comedian in the Vaudeville circuit. He made enough money to dress sharp and surround himself with pretty girls, and to buy a Pontiac Roadster. There’s a photograph of him leaning on the grill of the Roadster and wearing a light-colored three-piece suit and round tortoiseshell glasses. He would die quite young, of something that can now be easily cured with a good round of antibiotics, but they were not available to the public until a year or so after passed away. The only plausible outcome of a bout with the disease he contracted was a swift but painful death, or (if one was lucky) disfigurement and erasure of much of the quality of life.

My great-grandmother’s son Bobby had been an ice dancer and performed with the Ice Capades. I don’t remember how or when he died, but I do remember the sunroom off of my great-grandmother’s living room, which was filled with ferns. In the corner was a twin bed, made up neatly with a chenille bedspread. I remember her saying that was “Bobby’s Room”. That sunroom was one of the things in my great-grandmother’s house that frightened me. As a child I knew that “Bobby” was dead, and to hear someone refer to a dead person was scary. I didn’t care that the room was cheerful and alive with pretty green houseplants. Someone who was now dead had slept in there, and that turned the sunroom into a dark place.

My great-grandfather had died well before I was born. When he and my great-grandmother had first married they operated newspaper stands in train stations across the south and Midwest. He ran the till and stocked the shelves, and my great-grandmother prepared coffee and snacks to sell. After their children were born he traveled alone, sometimes leaving his family for great long stretches of time. She was used to his absence. My great-grandfather was from Johnson City, Tennessee. When he was small his young Irish mother left him at an orphanage, along with his brothers and sisters. She couldn’t afford to keep them. That is was what America was like before social services.

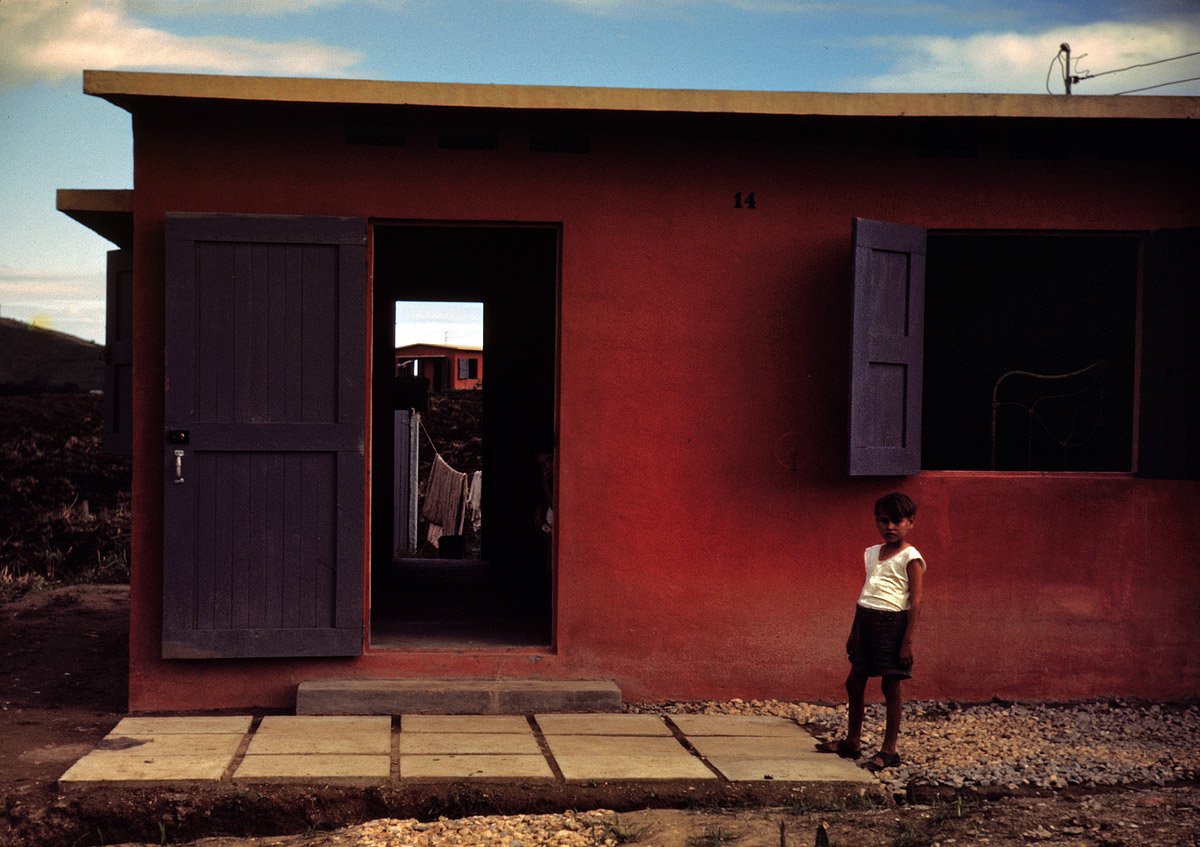

When my grandmother was small, my great-grandmother took her and her brother Bobby to Atlanta, to see the stars walk the red carpet outside the Fox Theater for the premiere of Gone With the Wind. My grandmother remembered seeing all of the stars of the film from her cramped spot in the huge crowd. She died recently, and the things she told me about her life (and what my father has told me), are swimming up from the dark parts of my memory like schools of bright silver fish. My grandmother, whose name was Juanita, was beautiful, strong, and modern. She lost her first husband in a car accident when my father was a boy. They lived in Puerto Rico at the time, where my grandfather worked as an accountant. My father, the oldest of four siblings when his father died, spoke Spanish then, and was surrounded by brightly painted buildings and tiny coqui frogs.